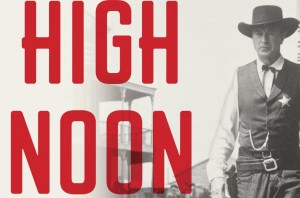

I recently finished reading a book about one of my all-time favorite movies—High Noon. In High Noon: The Hollywood Blacklist and the Making of an American Classic, author Glenn Frankel chronicles the creation of this film against the backdrop of one of the darkest periods in American history: political inquisitions by the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC) leading to the Hollywood blacklist and other infringements on civil liberty.

As the story unfolded, I grew increasingly troubled by the correlations to current events. The “threat” today, according to some, resides not in Communism but in the approximately 11 million undocumented immigrants who live in the United States. The situation is particularly heart-rending when we speak of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program and the so-called Dreamers, young people who have come to America with their parents. These young people do not remember any country but America, and they would be strangers in their so-called countries of origin.

As the story unfolded, I grew increasingly troubled by the correlations to current events. The “threat” today, according to some, resides not in Communism but in the approximately 11 million undocumented immigrants who live in the United States. The situation is particularly heart-rending when we speak of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program and the so-called Dreamers, young people who have come to America with their parents. These young people do not remember any country but America, and they would be strangers in their so-called countries of origin.

As I read and learn more about the plight of the Dreamers, I find myself thinking about my mother and her family. Her parents and oldest sister came to the United States from Italy in the early 20th century. Although my mother, her three other sisters, and a brother were native-born and her parents and oldest sister became naturalized citizens, my mother’s family faced extreme hardships and unimaginable—to me—racism and intolerance.

Sadly, their story was not an unusual one.

As each successive wave arrived in the United States, all immigrants faced hardships and prejudice. They lived in ethnic communities—partly because they felt comfortable living with people who spoke their language and partly because they were unwelcome elsewhere.

Yet these newcomers, once established, did not welcome those who followed.

Why did the Irish who arrived in the mid-19th century shut themselves off from the Germans and Scandinavians who came around the same time? Why did those people shun the Italians and other southern Europeans who came to America in the late 19th and early 20th centuries? Why did the Italians not welcome people from Eastern Europe who were fleeing turmoil and repression in their native lands in the mid- to late 20th century?

Today’s immigrants—both documented and undocumented—face the same barriers. Despite the Statue of Liberty extending her welcome from Liberty Island in New York Harbor, Americans do not always welcome newcomers.

We hear a lot about building walls along our southern border. While it’s true that nearly 80% of Dreamers’ families come from Mexico, the Pew Research Center notes that Asians are the fastest-growing group of undocumented immigrants. Overall, about 20 percent of DACA recipients come from Asia, with the majority from South Korea.

Yet even those coming to the United States from south of the border are doing so out of dire need and not a desire to take advantage of our country’s generosity. Just like my mother’s family and countless immigrants and refugees before them, they are looking for a place where they can live peacefully and raise their families in safety.

The immigrants and refugees coming to the United States from places like El Salvador and Honduras are fleeing terrible dangers posed by gangs, drug traffickers, and human traffickers. Those fleeing to our shores from the Caribbean must leave their homelands to escape continuing hardships due to natural disasters.

When we look at the bounties of America and compare that to what people have in many other nations, we cannot deny that we have much to share. One of my favorite patriotic songs has always been Woody Guthrie’s “This Land Is Your Land.” Do we believe this? Or do we want to share America only with those who look like us and think like us?

The word united is part of who we are as Americans. Unity is difficult to find in these troubled times. But it is not impossible.

I am looking for signs of hope.